When Hackney’s mayor spoke at the opening of the new Town Hall in July 1937, he expressed the hope that ‘the citizens of Hackney would look with pride and pleasure upon that great dignified centre of civic life’. (1)

To be honest, it’s not likely that they always did – ‘dignity’ is not a word that readily characterises the storm and stress of some of the borough’s later politics. But the Town Hall itself has stood as a worthy monument to the ideals of local government.

Time was when Hackney was a rather genteel village well beyond the grit and grime of the growing city but those days ended with the coming of the railway in 1850. When Mare Street was widened and as the tramways arrived in 1872, Hackney became an industrial and increasingly working-class suburb of London.

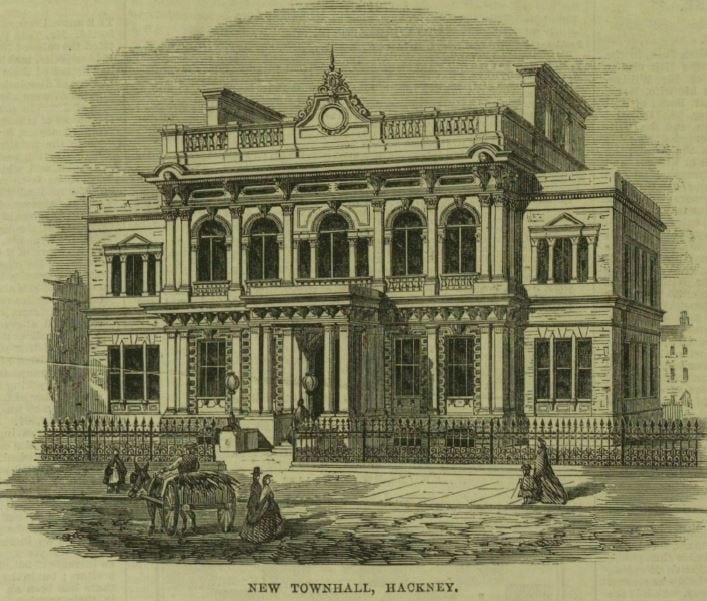

A complicated mix of vestries and ad hoc bodies governed the area until 1900. The first ‘town hall’ (built as a private home in 1802) was created in the mid-nineteenth-century as a vestry office for the parish of St John at the top end of Mare Street. It was replaced by a grander building further south on Mare Street in 1866 ‘of the French-Italian style of architecture, effectively treated in Portland stone’. (2)

This was ‘a modern structure … a striking contrast to many of the quaint old buildings which surround it’ but it was, apparently, soon found wanting. (3) And the more so as Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council was established in 1900 and as local government’s functions grew.

The new Council remained under Conservative control until – in that year of Labour triumph at the height of post-war discontent – Labour took control in 1919. But the Party lost every seat in the succeeding elections of 1922.

Thus it was a Conservative council which launched an architectural competition for a new town hall in 1934. The winners were Henry Lanchester and Thomas Lodge with a design – ‘conventional but not showy’ according to Pevsner – which cost £99,870: an Art Deco building of four storeys faced with Portland stone. (4)

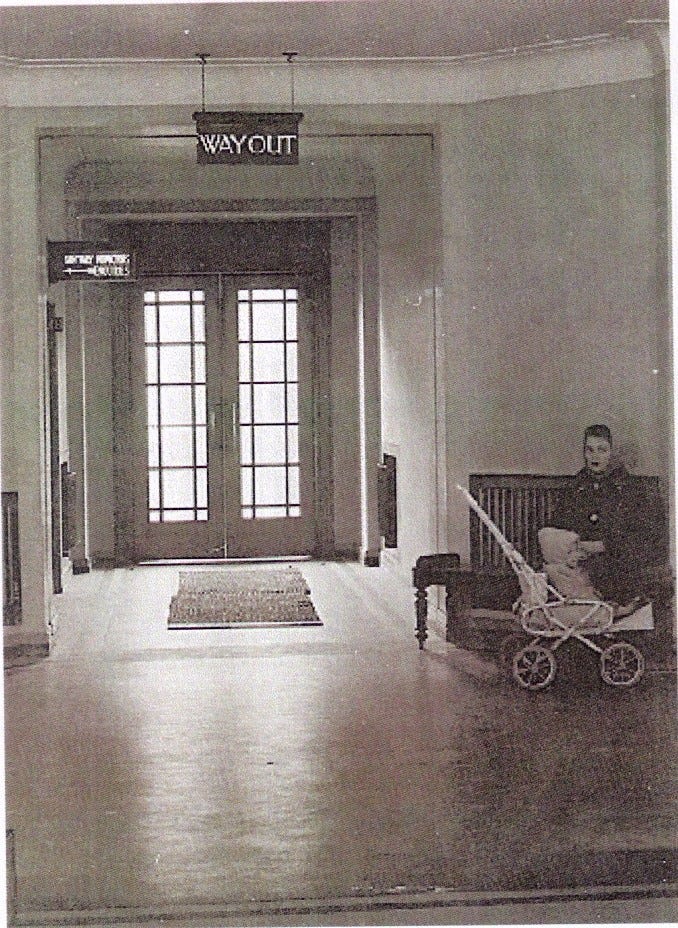

The old Town Hall was demolished and civic gardens and a war memorial constructed in front of the the new building. That contained, traditionally, a grand entrance hall and staircase leading to that heart of local democracy, the Council Chamber.

Ground floor offices contained the sinews of local government – the offices of the Borough Engineer, Medical Officer of Health, Borough Treasurer and the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages.

A second floor contained the Mayor’s Parlour and the offices of the Town Clerk. Modernity was trumpeted in the electrical thermal storage system and ventilation provided by electrically driven fans. There were even synchronised electronic clocks. (5)

Perhaps more impressive to the ordinary public was the new Assembly Hall built to the rear of the building, capable of seating 600 but with provision to be divided into three sections for a variety of other uses.

What remain outstanding are the Art Deco décor and fittings. Now fully restored, it is a beautiful building. And one that did bestow a dignity and grandeur to its civic role.

This was certainly the ideal of those city fathers (mainly fathers) who inaugurated the building in 1937. Ironically perhaps, this was now – and would remain – a Labour council. Labour had swept to power in Hackney in 1934. They maintained control until the abolition of the old Metropolitan Borough in 1965 with a near or absolute monopoly of seats for most of the period.

Thus it was that a Labour mayor, Alderman Herbert W Butler, and the then Labour Leader in the House of Lords, Lord Snell – born Harry Snell, the son of agricultural workers – presided over events on that July day.

Snell was an ethical socialist and the full flavour of that now largely forgotten politics is conveyed in his opening address. This was a building ‘devoted to the business of living one with another to the benefit of all’. It: (6)

represented something more than mere stone and wood put together; it embodied the ideal of social living which they would have to keep going. It was not the property of the Mayor and the Corporation; it was the property of the people of Hackney. It was for their use and to serve their needs, and what it did would react upon every home in every street in the borough. It was a symbol of their idealism and a focal point for the services of their great borough, and he hoped they would find in it an atmosphere of quiet dignity, purity of administration and of love for the purpose to which it was devoted.

At this time, Hackney’s politics might be best personified by Herbert Morrison. Morrison had been a Labour mayor of Hackney in 1920 in that earlier phase of Labour rule. He was now Labour leader of the London County Council but his brand of Labourism – ethical roots and bureaucratic leanings – lived on.

This politics survived and thrived in Hackney after 1945. But, for all its qualities and genuine pedigree, it became in its time a rather ‘Establishment’ politics focused on the bastions of old-style Labour representation – on the council, in the unions and in the tenants’ associations.

Meanwhile, Hackney – and the wider world – was changing. By the eighties, the enlarged Borough was one-third ethnic minority (that proportion is now nearer two-thirds). Women were another ‘minority’ who – in this new world – were not a part of old Labour’s ‘natural constituency’. And a new generation of university-educated, Marxist-influenced politicians emerged whose socialism branded old Labour as conservative, even privileged.

A New Left politics developed which properly focused on local issues of race and gender and advanced forms of ‘community development’ and decentralisation which challenged the structures of old Labour power. Its representatives took power in Hackney in 1982.

The vital question, of course was could they also deliver the bread and butter services vital to all sections of the community and which remained the staple of local government’s role as identified by Harry Snell fifty years earlier.

That’s as sympathetic a portrayal of the splits which ravaged Hackney’s local Labour politics in the eighties and nineties as I can come up with and, of course, it’s hugely simplified.

In headline terms, these splits were played out over rate-capping and the initial refusal of Hackney’s New Left to set a rate in 1985. The Council backed down after the Labour Group split almost fifty-fifty on the issue. They were seen, more discreditably, in later conflicts over personnel, policies and priorities in succeeding years. (7)

Luckily, this isn’t a blog about the intricacies of recent Labour politics. Suffice to say, a more stable, less ideologically-coloured Labour politics grew after 1997. Whether Harry Snell was turning in his grave in the meantime, you can judge.

Back to the Town Hall and back to local government and its more traditional functions. The Council’s new Service Centre – designed by Hopkins Architects Partnership, built at a cost of £43,733,000 and winner of a 2011 RIBA Award for architectural excellence – was opened in March 2010.

Its 15,000 square metres, arranged over five floors, house the Council’s administrative staff but, more strikingly, it acts – in the massive atrium containing the Council’s one-stop shop and public reception – as an innovative ‘focal point for the services’ of the Borough that Harry Snell might be proud of.

First published in November 2013

Sources

(1) Quoted in ‘Hackney’s New Town Hall’, Hackney Gazette, July 5 1937

(2) ‘The New Townhall, Hackney’, Illustrated London News, October 13 1866

(3) Edward Walford, Old and New London: Volume 5, 1878

(4) Elizabeth Robinson, Twentieth Century Buildings in Hackney, Hackney Society, 1999. Full architectural details of the Grade II listed building are provided in the English Heritage listing.

(5) Metropolitan Borough of Hackney, Programme of the Opening Ceremony of the New Town Hall, 3 July 1937

(6) Quoted in ‘Hackney’s New Town Hall’, Hackney Gazette, July 5 1937

(7) For a highly critical review of these politics, see David Walker and Rebecca Smithers, ‘Borough of hate and hit squads’, The Guardian, March 19, 1999

Especial thanks to the helpful staff of Hackney Archives for access to primary sources mentioned above and for permission to use the images noted above.

All reasonable efforts have been made to ascertain the copyright situation with these photographs and documents, but please contact Hackney Archives with any queries or further information.