The Aylesbury Estate, Southwark: ‘all that is left of the high hopes of the post-war planners is derelict concrete’

Tony Blair made his first public speech after New Labour’s 1997 landslide election victory in the Aylesbury Estate. This was a time of high hopes and Blair’s words capture the promise of the moment:

I have chosen this housing estate … for a very simple reason. For 18 years the poorest people have been forgotten by government … There will be no forgotten people in the Britain I want to build …

There are estates where the biggest employer is the drugs industry, where all that is left of the high hopes of the post-war planners is derelict concrete.

In the following year, the Aylesbury Estate was awarded £56m as one of 17 ‘pathfinder partnerships’ awarded cash under the Government’s New Deal for Communities scheme – ‘a key programme in the Government’s strategy to tackle multiple deprivation in the most deprived neighbourhoods in the country’.

That didn’t work out so well. As we’ll see, the Estate continues to languish though it is now – fifteen years on [in 2014] – in the early stages of a second regeneration project. Both – and the Estate itself – have been controversial.

The Aylesbury was ill-fated from the outset. It was built on a 60 acre site, replacing a rundown area of terraces, tenements and works – a massive canvas for what would become labelled (mistakenly) the largest social housing estate in Europe.

Designed by Hans Peter Trenton and a team of young architects in Southwark Council’s Department of Architecture and Planning, it reflects the modernist ideas of the day. Ben Campkin’s recent study of the Estate provides a better architectural description of their expression in the Aylesbury than I can: (1)

exposed concrete; ‘honest’ expression of structure; the repetition of geometric forms; and the elevation of slab blocks on piloti.

It would comprise around 2700 homes in all, accommodating a population of almost 10,000 at peak in 16 four- to fourteen-storey so-called ‘snake blocks’ including the largest single housing block in Europe. It was built by Laing – whose interests exerted a heavy influence over the external appearance of the Estate – using the Jespersen system: a large panel system using prefabricated concrete slabs.

Construction began in 1963. The collapse of the Ronan Point tower block in 1968 ensured this would be the last large-scale use of industrialised building methods.

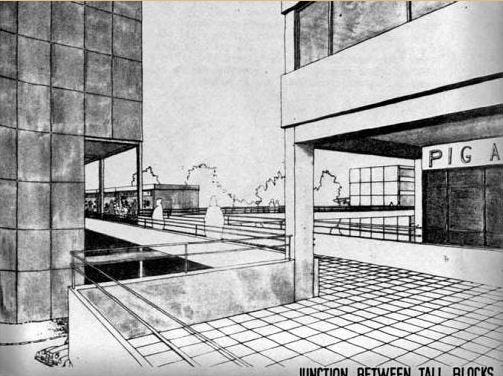

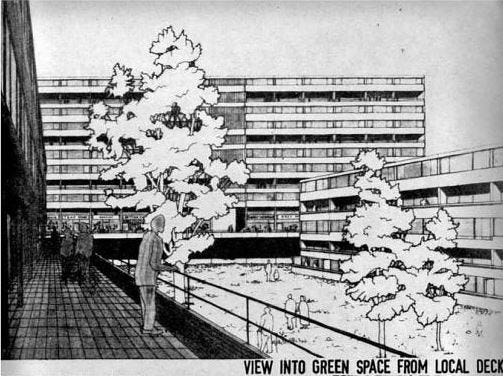

If the construction – and, arguably, the appearance – were industrial, the overall design of the Estate reflected communal ideals, most strikingly in its ‘streets in the sky’ which were intended to ease pedestrian movement across the Estate, free from the danger and noise of traffic.

Walkways linked the Estate’s blocks – ‘route decks’ at second floor level for movement between blocks which included space for shops and other community facilities and ‘local decks’, with play areas, within the blocks. Garaging and traffic movement took place below. (2)

The flats were large and nearly always far better accommodation than new residents had known before as these three reminiscences remind us: (3)

To get a council flat was to go up in the world.

Oh, yes. There’s no doubt about it. Coming to the new estate for most of us at that time was like Shangri-La

We thought we was moving into Buckingham Palace!

But the overall ‘feel’ of the Estate was problematic from the outset. The architectural press described it as ‘drab’ and ‘monotonous’.

Even as the first residents moved in and the Estate was formally opened by Anthony Greenwood, Labour’s Minister of Housing and Planning, in October 1970, one local Tory councillor described it, unoriginally, as a ‘concrete jungle … not fit for people to live in’. (4)

There were early design problems too – the walkways required noise insulation, some finishings were of low quality, little was spent on shared facilities such as lifts and open space

Southwark’s architects recognised this themselves and blamed the £1m cost-savings forced on the project by the Government prior to construction: (5)

There is little doubt that the public areas are the least successful part of the Development. The lack of finishes and the poor quality of many of the materials provided has provided a very drab environment … This seems almost to have provoked mistreatment and vandalism. The extensive areas of bare concrete, asphalt, and cheap obscured glass, contribute to the overall feeling of low cost Local Authority housing, and it is almost an insult to the many tenants who are proud of their homes … It is essential that adequate financial backing should now be given to put these deficiencies right. Failure to do so will result in the Estate rapidly becoming a slum.

By 1976, the Council had spent £2.6m on basic remedial work. And when Southwark’s housing chair formally ‘topped out’ the Estate in September that year, the local newspaper headlined its report ‘Epitaph to the “Nightmare” Estate’. (6)

By the 1980s, the Estate was notorious for crime and anti-social behaviour and relished by the media as a potent symbol of the ‘Broken Britain’ of the day. Naturally, it also became a poster-child for theorists of ‘defensible space’ including Oscar Newman himself who slated the Aylesbury’s design in a 1974 BBC documentary.

And, later, when Alice Coleman noted that ‘the notorious Aylesbury Estate has 18 km of walkways making it possible to reach 2268 dwellings from any single entrance without having to set foot on the ground’, she didn’t mean it as a compliment. (7)

That correlation might not mean causation, that similar problems bedevilled suburban ‘cottage estates’, that deeper social and economic causes might be at play was ignored – the superficial plausibility of the argument won the day and did, in its way, its own damage.

And the feelings and experiences of the actual residents were mixed and more complex. Most liked their flats – they remained for the most part good accommodation. Many liked their neighbours and resented the bad press the Estate received. But the crime and fear of crime were real as were the difficult life circumstances of many of the residents.

And although, it’s a desperately unfashionable thing to say, Tony Blair was right to highlight the problems of the Aylesbury – and other similar estates – and to promise concerted, collective action to rectify them. That would prove a rocky path, however. We’ll look at that in the next post.

This post was first published January 2014 as was Part II to follow. For more recent analysis, I’d recommend Michael Romyn’s book, Aylesbury Estate: An Oral History of the Concrete Jungle, published in 2020 which I reviewed in this post at the time.

Sources

(1) Ben Campkin, Remaking London: Decline and Regeneration in Urban Culture (2013)

(2) London Borough of Southwark Department of Architecture and Planning, Aylesbury Redevelopment, ND

(3) Long-term residents of the Estate quoted in Sarah Helm, ‘Lost souls in the city in the sky’, New Statesman, 17 July 2000 and Richard Godwin, ‘We shall not be moved: residents give their verdict on life on the Aylesbury Estate’, Evening Standard, 26 March 2013

(4) Cllr Ian Andrews, quoted in ‘”Showpiece” Estate is unfit to live in, says Tory councillor’, South London Press, 16 October 1970

(5) Borough Development Department, Aylesbury Development in Use, May 1973

(6) South London Press, 10 September 1976

(7) Alice Coleman, ‘Design Influences in Blocks of Flats’, The Geographical Journal, vol. 150, no. 3, November, 1984

My thanks to the Southwark Local History Library for help in accessing the primary sources noted above.

I remember, shortly after Tony Blair’s Pathfinder news, a representative group of Aylesbury residents coming on a 3 day design event I was part of running at the National Tenants’ Resource Centre in Chester. They were so happy, full of hope and so determined that, at last, their place was about to be sorted out and with their full involvement. That was how they felt then anyway.