Excuse me if I begin my blog this week with a lengthy quote. It’s just that it seems to me to convey something simple and powerful about the drive and vision of a group of people who dreamed of nothing less than transforming a slum into a garden city.

If elected it will be our main aim to make Bermondsey a fit place to live in. We shall do everything we can to promote health, to lower the death rate, and to increase the well-being and comfort of the 120,000 people who live here.

We will not allow our district to continue to be a by-word among the Boroughs and to be vilified by the Daily Press as a horrible, evil-smelling, slum-ridden and unlovely place. We will do what is possible to cleanse, repair, rebuild and beautify it, and to make it a city of which all citizens can be proud. Bermondsey is our home and your home. We will strive to make it a worthy home for all of us. This is our conception of the object and purpose of local government …

Those were the opening words of the Bermondsey Labour Party’s address to local electors in November 1922. The party won 38 seats and an overall majority on the council which it retained till the borough’s abolition in 1965.

If ever such ambition was needed, it was needed in interwar Bermondsey. It was one of the smaller London boroughs but one of the most densely settled. Of its 1300 acres, 400 consisted of docks and warehousing. In the remainder, industry sat cheek by jowl with terraced housing and courts. In 1922, just 8.6 acres of the borough were public open space.

If such conditions oppressed local residents, they outraged the husband and wife team, Alfred and Ada Salter, who spearheaded local Labour politics. Alfred was the local GP, Ada was a social worker, both were ardent Christian socialists. Their concern for the health and moral well-being of the people joined irresistibly in their fight for social justice.

Of those who had created this Bermondsey – ‘one huge slum’ as he described it unapologetically – Alfred could only lament:

They did not realise that they had cut off the people from the chiefest means of natural grace. They did not appreciate the curse and cruelty of ugliness.

And it was Ada who would do all in her power – all that local government allowed – to create grace and beauty in Bermondsey. One of the first actions of the new Labour administration was to set up a Beautification Committee and Ada chaired it for eleven years. Its first meeting in January 1923 announced its goal – ‘Fresh air and fun’ – and its agenda.

That agenda was ambitious. Council officers were to identify any waste ground –private or public – that could be planted with trees and shrubs and ornamented with tubs, rockeries, fountains and statuary.

The council was to provide window boxes free of charge to any resident that requested them and organise horticultural shows and gardening competitions to encourage those with green fingers.

Leisure would be catered for by a permanent bandstand and regular summer concerts. ‘Healthful exercise and bodily development’ would be promoted by providing new winter gardens and ‘other suitable places of public resort which can comprise gymnasia, bowling alleys, fives courts and open air baths’.

Even the borough’s public conveniences – an ugly necessity under the jealous eye of the Public Health Department – were to be made easier on the eye by screens of foliage and shrubs. The Committee would also seek powers to restrict unsightly advertising, dumping and constructions – in fact, ‘anything offensive to good taste.’

Not all of this was possible. The more elaborate plans for fountains, statues and the like just didn’t happen. The Town Clerk was adamant that the council’s powers did not allow free window boxes but free plants and compost were apparently permissible. Bermondsey never got its winter gardens though the London County Council did build a lido in Southwark Park in the 1930s. Those draconian powers restricting offences to good taste weren’t possible either though the railway companies were persuaded to better maintain the sidings which were a prominent feature of the borough.

Still, what was achieved was impressive: (1)

Bermondsey became a place of unexpected beauty spots. Amidst soot-grimed buildings one suddenly came upon splashes of brilliant colour, red dahlias, yellow daffodils They were like vases of flowers in a dusty room.

The Observer claimed that ‘outside the Royal Parks it would be difficult to find anywhere such masses of colour’. The Labour councillor who proclaimed in 1928 that ‘what was good for the West End was equally good for the East’ would have been proud of this literal vindication of principle.

Ten thousand trees were planted and seventy of the eighty grimy miles of street in Bermondsey became tree-lined. Most of the trees and shrubs – in the huge numbers that the Beautification Committee’s plans demanded – came from Fairby Grange in Kent, the house and gardens purchased by the Salters and given to the council as a convalescent home for nursing mothers and their children.

To those who complained of the expense of all this tree planting, the Council simply pointed out that the work – subsidised by a 60 per cent subsidy from the Unemployment Grants Committee – provided work for those who would otherwise be on the dole.

The dense, built-up nature of this inner London borough limited what could be provided in terms of additional open space but the existing parks and gardens – mainly former churchyards – were greatly improved in appearance and facilities. The pride and joy here was the large and elaborate covered slide in St James’s churchyard which had actually been donated by Peek, Freans, a large local employer, in 1921. Otherwise, the scope was limited and only three small open spaces were acquired and ‘beautified’ by the council in the twenties.

In fact, it is the intense quality of Bermondsey’s vision and the detail which capture the imagination. The Council was helped here by the dedication of two Superintendents of Gardens, Mr Aggett and Mr Johns – such proprieties of title were observed in those days – for whom beautification was both a labour of love and a matter of deep professional pride.

There’s no glamour in the dry detail of council staffing but it’s worth pointing out that the Beautification Department employed 36 people in 1926 and a further eight who were full-time caretakers of the parks and open spaces.

Local Labour’s 1925 manifesto uses a phrase that rings strangely today but the ‘mass upliftment’ they proclaimed was a two-way street. The socialists of the day were both practical reformers and moralists. They saw no contradiction in the two – betterment was something which both came from and was ‘done to’ the poor. This was a community which treated morally would act morally. This was the radical respectability of the Salters and of the Labour rank and file in action.

In 1928, Alfred Salter, celebrating six years of Labour rule, stated:

The Party is like this because it is inspired by idealism, because it has a vision, because its efforts for human welfare are part of its religion. A great spiritual motive is working itself out in devoted service and practical achievement.

Trees, window boxes, flower beds and slides, even two new strains of dahlia (Salter’s favourite flower) named the Rotherhithe Gem and the Bermondsey Gem and created by Mr Johns, all played their part in this.

As Elizabeth Lebas argues: (2)

In Bermondsey, ‘beautification’ was not a substitute to political action, but a political action in itself.

And it was, I hope you agree, a rather beautiful form of political action.

First published April 2013

Sources:

(1) Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: the Life of Alfred Salter (1949)

(2) Elizabeth Lebas, ‘The Making of a Socialist Arcadia: arboriculture and horticulture in the London Borough of Bermondsey after the Great War’, Garden History, vol 27, no 2, winter 1999.

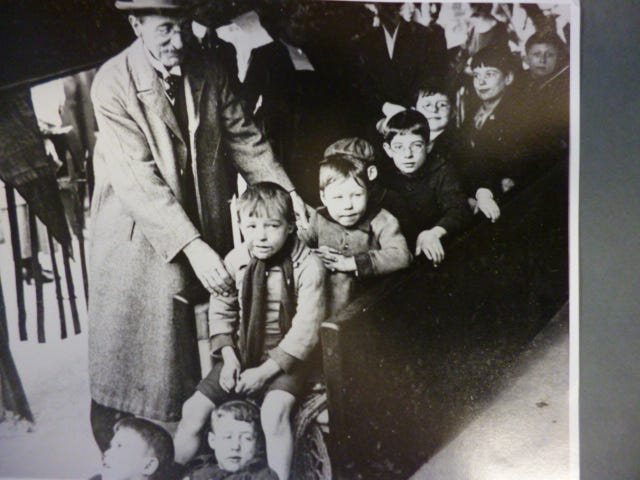

All the historic images are taken, with permission, from the superb collection of photographs held by the Southwark Local History Library and Archive. Most of the direct quotations above are taken from contemporary newspapers and election leaflets held in the library’s cuttings collection. A big thank you to library staff for their generous assistance in this and related posts on Bermondsey.

The other major source is the very useful and interesting article by Elizabeth Lebas referenced above.

The Salters were absolute heroes in Bermondsey. My Nan (born 1914) was a patient of Dr Salter as a baby - he told her mother off for swaddling her too tightly, saying she needed fresh air and room to kick her legs!

The free window-boxes (even though they didn't quite come off) were a lovely - and inspired - idea.