The realisation that behind this stupendous tour de force lies only the domestic intricacies of municipal housing risks turning the whole display into an absurd melodrama, a folie de grandeur.

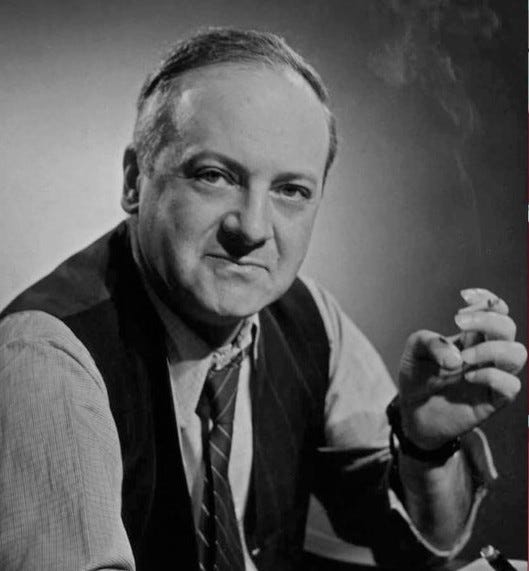

These are the words of John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin’s friend and biographer, in describing the architect’s last major work, the Cranbrook Estate in Bethnal Green. (1)

To be honest, the passer-by on Roman Road might be forgiven for seeing rather more ‘municipal’ than ‘grandeur’ with a quick glance but, in conception and design, the Cranbrook Estate deserves closer attention. It remains a monument to post-war ambitions to house the people and a testimony, in particular, to the vision of the tiny borough of Bethnal Green.

Bethnal Green covered a little over a square mile. And that – despite their proximity – was probably its only resemblance to the City of London. Bethnal Green was a working-class borough with a population in 1955 of around 54,000 – half that of 1931. All thirty seats of the Council had been held by Labour since 1934 and would remain so till the abolition of the borough in 1965.

That falling population reflected the deliberate slum clearance of the 1930s and the Luftwaffe’s unofficial efforts during the London Blitz. A total of 3120 houses had been destroyed in the war; thousands more were damaged. Housing was a pressing issue. (2)

The first priority was to repair those houses capable of repair. By 1953 this was largely complete and the London County Council and Metropolitan Borough Council refocused their efforts on slum clearance. Both had already built homes in the borough too – the LCC over 800 by 1951, Bethnal Green 643 by 1953.

The Borough’s ambition to build and build well is nowhere better illustrated than the panel of architects it appointed in 1951 to design its new housing. It was, as the list demonstrates, truly a rollcall of some of the brightest and best architects of the day:

Messrs. Donald Hamilton, Wakeford & Partners

Messrs. Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin

Messrs. Powell & Moya

Messrs. Yorke, Rosenberg and Mardall

Messrs. Fry, Drew, Drake and Lasdun

The driving force here seems to have been Peter JH Benenson, an alderman of the council from 1949 to 1953 (his wife Margaret Susan Benenson, née Anderson, was elected a councillor in 1953). Benenson was appointed a member of the Housing Committee and was to become its vice-chair. No doubt, his elite social connections and personal friendship with Lubetkin were a factor in the Borough’s choice to appoint leading contemporary architects to design its housing but it’s a reminder too that – to paraphrase a famous saying of Lubetkin – that nothing was thought ‘too good for ordinary people’. (3)

In this context, Pevsner comment on the ‘more sympathetic detailing’ of the Borough’s housing compared to that of the LCC, hardly seems surprising. (4) But the height of the Council’s ambition came with the Cranbrook Estate started in 1955.

In that year, Bethnal Green appointed Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin (a regrouped version of the Tecton Group which had designed the Spa Green Estate in Finsbury before the war) as architects of the scheme and approved its first stage. The Council also stipulated in draconian but necessary terms – given their intentions – that no applicants on the waiting list would be granted any of the new-build homes; it would all go to those living in areas to be cleared.

A year later, Bethnal Green Council declared 17 acres of decayed Victorian terraces, workshops and one large factory a clearance area. Compulsory purchase was agreed by the government in 1957. A total of 1032 people in the clearance areas and a further 624 in adjacent streets would be displaced. (5)

Construction began shortly after. The first units – Holman House, a five-storey block of 48 flats over a frontage of 12 shops, Tate House, 14 old people’s bungalows and Stubbs House, a two-storey block of old people’s dwellings – were officially opened by the mayor in March 1963. (6) The Estate as a whole was officially opened in January 1965 and completed in 1966.

The new Estate – in plain numbers – comprised two fifteen-storey blocks of 60 homes each, two thirteen-storey blocks of 52 homes each, two eleven-storey blocks of 44 homes each and five four-storey blocks of 28 homes. With ancillary dwellings, there were 529 new homes in total – 43 bedsitter flats, 115 one-bedroom flats, 271 two-bedroom flats and 100 three-bed flats. This is one and half times the size of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. (7)

But the numbers alone don’t tell the story – the genius of Cranbrook lay in its overall design. This was Lubetkin’s vision, very much his: (8)

I always had the impression that he was the boss. We all used to come, all the mums, and meet him and he’d say: “How’s things working?” He’d come in and have a biscuit and a cup of tea and he’d say that no matter what flat he went into, his décor went with the furniture. He was very proud that everything went together.

He’d come up to London each month, his ‘sketchbook bulging with plans’. In overall terms, the Estate was, according to John Allan, his ‘most ambitious achievement in urban orchestration, an essay in controlled complexity’.

The ensemble of six towers and five medium-rise blocks were arranged geometrically, set along two diagonal axes – pedestrian walkways which echoed the earlier street pattern. The buildings progressively reduced in height from 15 storeys to 13 to 11 in the towers to five in the block of flats and shops on Roman Road, then to four in the series of maisonettes and to two, and finally – in a conscious diminuendo – to one storey in the old people’s bungalows on the Estate’s perimeter.

In James Meek’s words, the blocks were spaced apart and so angled that one face would always catch the sun and shadows cast would ‘rotate like the spokes of a wheel’.

In the original design, one of the avenues was to lead directly at its north-western corner into Victoria Park but the Council couldn’t purchase the intervening land. Instead, Lubetkin designed an elaborate trompe l’oeil – a tapering ramp and series of diminishing hoops to give the illusion of distant vista. This survives in vestigial form but is now looking rather forlorn.

There have been other changes too. Some of the élan of Lubetkin’s original design has been lost. Those diagonal axes became a figure of eight. The tower blocks now have blank steel shutters erected across the deep openings which originally scored their façades; the green concrete bosses and glass beads which studded the façades have been replaced by aluminium boxes; white pipework scars their exterior. Parts of it are clearly in need of refurbishment. The passer-by might be forgiven for seeing the Estate as a little more ordinary than it actually is.

But Cranbrook must ultimately be judged as living space rather than architecture. And, in these terms, it seems to have worked well. Doreen Kendall, one of the original residents of the Estate and still living there:

loved it. I absolutely adored it. We had central heating so we didn’t need to light a fire any more. My husband thought we’d moved into a ship. All the walls were painted grey, battleship grey. Everything was grey except the wall where my books are and the bathroom, which was red, a dusty red.

And writing in 1993, one commentator concluded that Cranbrook ‘seems unaffected by the ills that beset other inner-city estates’. (9) Perhaps this reflected the Estate’s demography. Kendall, then chair of the tenants’ association, stated:

We’re a very close community. We all came out of the same clearance areas. Children have grown up together and intermarried; some of them still live here

Others too have very positive memories: (10)

I have to say I loved growing up there and have very fond memories of playing out with friends and certainly always felt safe! Our flat was spacious – my bedroom now in a four bed house is about half the size of the bedroom I had in Offenbach House.

More recently, when one resident spoke of their fear of crime on the Estate, others were quick to defend the safety and friendliness of Cranbrook – though a few knew of particular ‘problem families’ who did cause trouble.

And that brings our story pretty much up-to-date. The Estate is now managed by Tower Hamlets Homes, an ‘arms-length management organisation’ of Tower Hamlets Council. That, however, was a close-run thing. In 2005 it was proposed to transfer ownership to the Swan Housing Association but a campaign by Defend Council Housing and then local MP George Galloway secured a 72 per cent tenant vote in opposition.

The campaign against ‘privatisation’ as it was described by opponents was hard-fought. The Council claimed it could not fund necessary repairs and refurbishment if the Estate remained in Council hands; Mr Galloway claimed that housing associations existed ‘for their own corporate reasons and their own corporate benefits’. That was unfair but the result of the vote did reflect tenants’ fears about rents and tenancy conditions under new ownership and a sense that Council control offered more democratic influence over the management of their homes. (11)

In this context, Lubetkin’s disillusion with municipal design – which came to a head with the rejection of his plans for Peterlee – seems disingenuous. Ultimately, council housing has been less about ‘grand designs’ than about providing decent homes for ordinary people.

But Lubetkin was an idealist – an ‘artist engineer’ who believed in the power of technology and design to transform and improve people’s lives. And his lament for a time when the state and architects and planners shared a common vision of a better world and their power to create it retains its power: (12)

We came to feel that the symbolic value of modern architecture, which had been the basis of all its hopes and expectations, was steadily evaporating – not only because of bureaucracy’s effects in “clipping one’s wings” – but also because the public themselves became more and more disillusioned with any idea that art or architecture could lift them up or foreshadow a brighter future. Instead of looking at architecture as the backdrop for a great drama – the struggle for a better tomorrow – they began to see only the regulations, housing lists, points system, etc., and so only expect “accommodation”. It was this slide of public opinion – perhaps even more than the tedium of bureaucracy that finally disarmed the exercise as far as I was concerned. It made all our efforts seem so hollow

First published in April 2014, I have updated it to include details of the architectural panel appointed by Bethnal Green Metropolitan Borough Council in 1951. Some later photographs added.

Sources

(1) John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin. Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (1992)

(2) David Donnison, ‘Ch. 5 Slum clearance begins again in Bethnal Green’ in Donnison and Chapman, Social Policy and Administration (1965)

(3) I’m very grateful here to Thaddeus Zupančič whose research has supplied these details. Benenson came from an upper-class Jewish family (he later converted to Roman Catholicism) and was privately tutored by WH Auden before entering Eton College. An unsuccessful Labour parliamentary candidate, he founded Amnesty International in 1961.

(4) Quoted in TFT Baker (ed), ‘Bethnal Green: Building and Social Conditions after 1945’, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998)

(5) Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green, The Redevelopment of the Cranbrook Street Area (1960)

(6) Bethnal Green Civic News, no 2, April 1963

(7) Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green, Programme of the Official Opening of the Cranbrook Estate by the Rt Hon Lord Beswick, 30 January 1963

(8) Resident Doreen Kendall quoted in James Meek, ‘Where will we live?’, London Review of Books, Vol. 36, No. 1, 9 January 2014

(9) Deborah Singmaster, Architects Journal, 15 December 1993

(10) See the comments on LoveLondoncouncilhousing, ‘Cranbrook Estate’, posted September 3, 2009, and read the blog for more photos and analysis. [Website closed]

(11) Mark Leftly, ‘Charm offensive’, Building.co.uk, issue 48, 2005

(12) Lubetkin quoted in John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin

I’m grateful as always to the helpful staff of the Tower Hamlets Local History Library for their help in accessing their excellent resources.