The Hulme Crescents, Manchester: bringing ‘a touch of eighteenth century grace and dignity’ to municipal building

In 1978 the chair of Manchester City Council’s Housing Committee described the Hulme Crescents development as an ‘absolute disaster – it shouldn’t have been planned, it shouldn’t have been built’. (1) By that time, the estate was already a byword for the failure – worse, the inhumanity – of sixties’ mass public housing. That reputation has lingered long after the demolition of the Crescents in 1994.

This won’t be a revisionist piece but let’s at least look a little more closely at what went wrong.

As we saw when we looked at the city’s early municipal housing in Ancoats, Manchester was the ‘shock city’ of the Industrial Revolution. Hulme was also the home of many of those first industrial workers. In 1914, a Special Committee of the City Council reported a population of 63,177 living there in just 13,137 homes, 11,506 of which lacked baths or any laundry facilities.

In 1934, the area was designated for slum clearance – the largest such area in Britain. But little was done before the outbreak of the Second World War and it was the war itself which would accelerate demands, expectations and plans for change. A City Council report in 1942 declared 68,837 houses in Manchester were unfit for human habitation; a total of 76,272 new homes would be required to meet long-term needs.

That cause was taken up in the 1945 City of Manchester Plan, scathing in its condemnation of ‘the meanness and squalor of Hulme’ and Manchester’s other industrial suburbs – ‘the drab streets, the dilapidated shops, the sordid public houses, the dingy schools, the sulphurous and sunless atmosphere’.

Radical action was needed – and promised. But the city was clear that flats and high-rise were not the answer: (2)

It would be a profound sociological mistake to force upon the British public, in defiance of its own widely expressed preference for separate houses with private gardens, a way of life that fundamentally out of keeping with its traditions, instincts and opportunities’

Manchester’s model was its own Wythenshawe Estate – a spacious out-of-town suburb built on garden city principles, begun in 1927. The Council proposed 40,000 new homes in similar schemes. But neighbouring authorities – in particular, affluent Cheshire – feared this urban incursion and the uncouth incomers they felt it would bring and were far from cooperative.

Slum clearance began again in Manchester in 1954 but the programme – aiming to demolish 7500 houses a year – faltered as the rate of new-build dried up to little over 1000 a year by the end of the decade.

A similar picture existed at national level. Council house completions had fallen to half the 229,000 peak achieved in 1953. But the sense of urgency persisted. Around 1m slums remained and just 30,000 were being cleared each year. A Conservative government committed in its White Paper of 1963 to building 350,000 new homes annually. It was outbid the following year by the incoming Labour administration’s promise of 500,000.

Such ambition demanded new methods and ideas. Low density suburban estates hadn’t delivered the numbers and were, in any case, unpopular with some tenants and hamstrung by planning restrictions. Industrialised and system-building methods seemed to offer a solution.

The Ministry of Public Building and Works took specific responsibility for promoting: (3)

the use of new and rapid methods of construction, standardising the use and production of building components to the greatest possible extent, and securing the widespread dissemination of the best modern practices.

The Conservative Government expected 25 percent of local authority housing output to be constructed using industrialised methods, a proportion raised by Labour to 40 percent . Councils which ‘seemed to be co-operating were “rewarded” in terms of enhanced capital allocations, speeding approvals, etc.’

That pressure, those dynamics – local and national – came together to create the Hulme Crescents.

In 1962, the City Council announced a five-stage programme to build some 10,000 new homes over a ten-year period. At peak, 4000 homes would be cleared and built each year. It began relatively modestly – 248 maisonettes, flats and houses to be built at a cost of £1m. It grew in 1964 as rebuilding commenced with 5000 new homes and Manchester’s first high-rise – a series of thirteen-storey tower blocks.

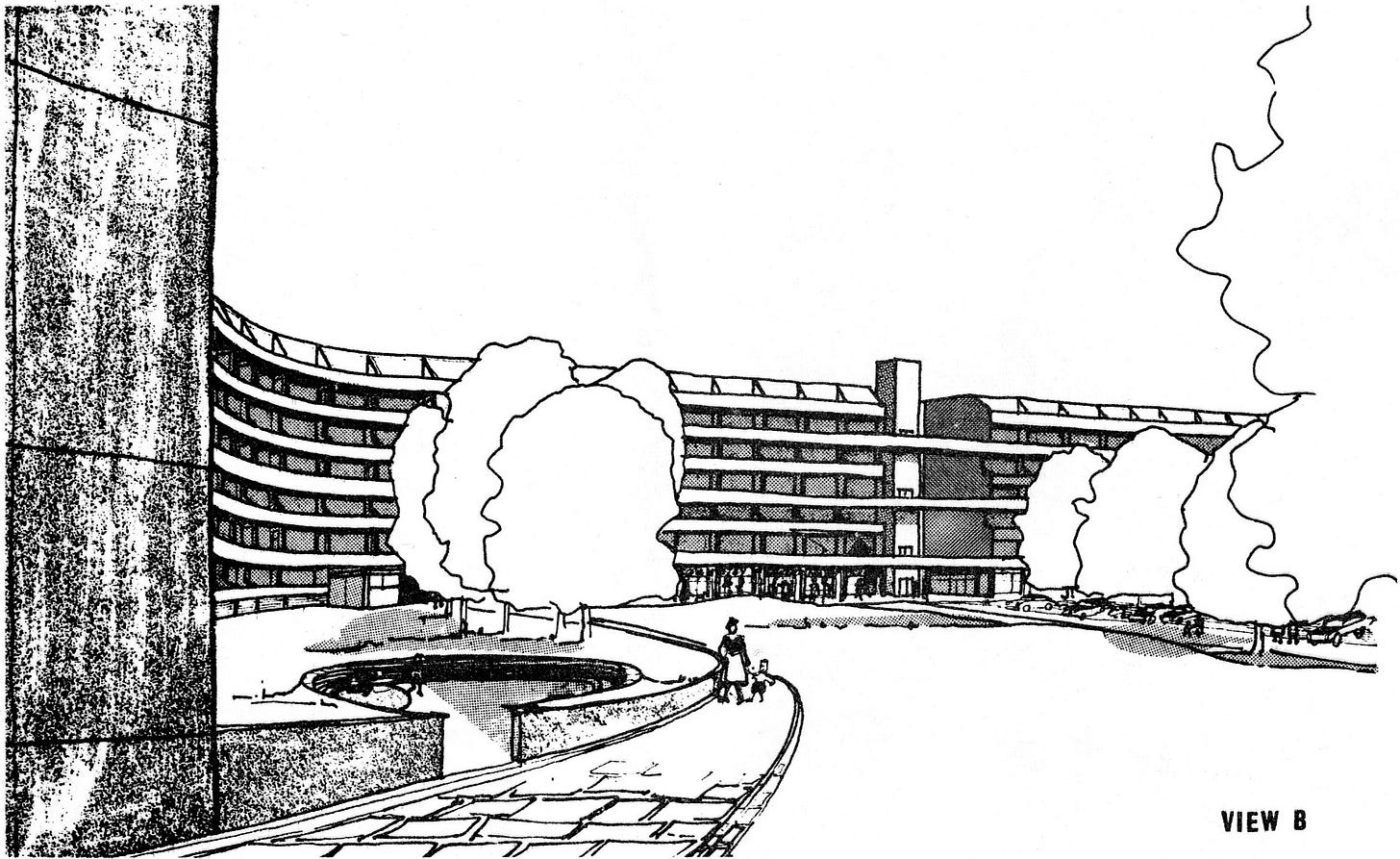

It culminated in its final stage, Hulme V, unveiled in October 1965, with what the then chair of the Housing Committee, Eric Mellor, claimed would be ‘one of the finest schemes in Europe’ – four deck-access six-storey crescent blocks – 924 homes in all – at a cost of over £3.8m.

This wasn’t cheap but it reflected what the Council felt to be the ambition of the development. In design terms, it had been promised: (4)

a high quality of finish, both internally and externally…obtained because structural components, fittings and services will be manufactured and supervised under factory conditions and not subjected to climatic and other hazards of an open site.

In planning terms, this was to be ‘an urban environment on a city scale’ in a form which would promote ‘greater choice of friends among neighbours’ and ‘easy contact’ for elderly people ‘with the passing world’.

And Manchester felt it had been true – in part at least and as far as circumstances allowed – to its earlier ideals in creating inner-city ‘streets in the sky’ which would foster a community atmosphere akin to the terraced housing that had been cleared.

The Manchester Evening News was gushing in its praise: (5)

(Of) all redevelopment schemes that will rejuvenate the Britain of tomorrow, Manchester’s plan for Hulme stands out boldly. For it is unique. Here is a fascinating concept which should make proud not only the planners but the citizens. That the design for a thousand maisonettes in long curved terraces will give a touch of eighteenth century grace and dignity to municipal housing is welcome indeed. But above all the plan is realistic … Thank goodness someone has been using both imagination and common sense in planning homes.

This was an echo of the rhetoric and vision of the scheme’s designers, Hugh Wilson and Lewis Womersley – Wilson had been the chief architect of Cumbernauld New Town and Womersley responsible, as City Architect, for the Park Hill Estate in Sheffield: (6)

We feel that the analogy we have made with Georgian London and Bath is entirely valid. By the use of similar shapes and proportions, large-scale building groups and open spaces, and, above all, by skilful landscaping and extensive tree planting, it is our endeavour to achieve, at Hulme, a solution to the problems of twentieth-century living which would be the equivalent in quality of that reached for the requirements of eighteenth-century Bloomsbury and Bath.

The Crescents were named after the four major architects of Georgian Bath; Charles Barry, John Nash, Robert Adam and William Kent.

Construction began in 1969 and was completed – using those state-of-the-art system-building methods of the day – rapidly. The topping out ceremony for the Crescents took place on 14 July 1971 and early reactions were positive.

I’ve spent some time on all this background and many of you will be more interested in the unfolding disaster which followed. Still, it seems to me to be important to understand the context and, yes, the ideals which shaped the estate. This context doesn’t excuse the mistakes that were made but it should, at least, help us move beyond the simple desire to blame and condemn.

So what did go wrong? We’ll examine that in next week’s post.

First published in March 2014; additional images added.

Sources

(1) Councillor Allan Roberts, interviewed in ‘There’s No Place like Hulme’, World in Action, 10 April 1978.

(2) Rowland Nicholas, The City of Manchester Plan (1945)

(3) Geoffrey Rippon, MP, Minister of Public Building and Works, quoted in AMA, ‘Defects in Housing Part 2: Industrialised and System Built Dwellings of the 1960s and 1970s’ (1984). The quotes and detail which follow also come from this source.

(4) The architects’ report quoted in Edward Hollis, The Secret Lives of Buildings (2011)

(5) Much of the detail above and contemporary quotations are drawn from Peter Shapely, ‘The press and the system built developments of inner-city Manchester, 1960s-1980s’, Manchester Region History Review, 2004, and the same author’s, ‘Social Housing in Post-war Manchester: Change and Continuity’ (April 2013)

(6) Quoted in Ed Glinert, The Manchester Compendium: A Street-by-Street History of England’s Greatest Industrial City (2008)

Images, where credited, are taken from the Flikr set on Hulme’s redevelopment posted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Visual Resources Centre.

Always been fascinated by this development. Very excited to hear about how it all went wrong!