The Norris Green Estate in Liverpool has been in the wars. If you’ve read some of the press coverage over recent years, that might seem an almost literal statement but the reality is that the Estate simply represents all the hopes and fears that have been invested in social housing over the decades. It deserves to be better understood.

In many ways, its story – if you’ve been following this blog – will seem typical. The Estate was born in the interwar period when central and local government shared a mission to house those we must now call ‘the hard-working people’ of Britain decently.

Nowhere was this more necessary than Liverpool. The city was the first to build council housing and its efforts before the First World War were impressive. But still, in 1919, 11,000 families – over 6 per cent of its population – lived in one-room dwellings. It was estimated conservatively that 8000 houses were needed immediately and 1000 a year thereafter to ensure a growing population adequate accommodation. (1)

In the post-war drive to build, the Conservative-controlled council (it would remain in Conservative hands until 1955) built 5508 houses under Addison’s 1919 Housing Act – more than any municipality in the country. But the city couldn’t rest on its laurels. In 1924, its overcrowding was three times the national average and there were 20,000 names on the council house waiting list.

In October, the City Engineer John Brodie presented plans to build 5000 new homes. Lancelot Keay was appointed his chief architectural assistant and would become a high-profile Director of Housing in 1929.

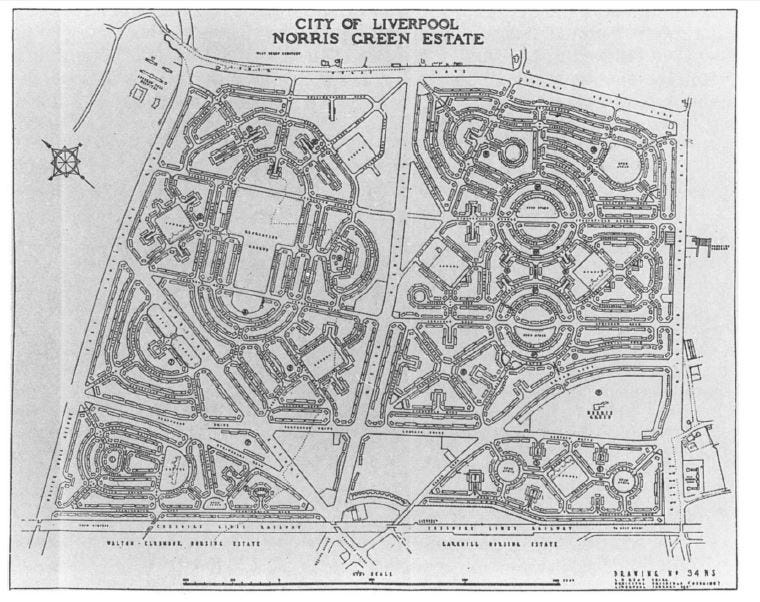

Land was purchased on the north-eastern fringe of the city – 650 acres (of which 470 lay in the neighbouring Sefton Rural District Council until incorporated into the city in 1928) which would form the new Norris Green Estate. Building began in June 1926.

Within three years, the Estate contained a population of 25,000. Eventually, there were some 7689 homes housing a population of over 37,000. This was a phenomenal achievement but not without problems.

All the homes – 4,724 parlour, 2,965 non-parlour – had three bedrooms. The non-parlour had a downstairs bathroom but all benefited from electricity and hot water, front and rear gardens and woodwork painted in regulation Corporation green and cream. Most were built of unglazed brick but, to build faster and more cheaply, the Estate also featured some 3000 ‘Boot and Boswell’ pre-cast concrete homes. We’ll return to these. (2)

The urgent rush to build left the Estate’s infrastructure severely underdeveloped for some time. Early streets were unpaved – wooden planks acted as makeshift walkways – and the first shops didn’t open – in the Broadway – until 1929. This gave Liverpool’s unofficial entrepreneurs ample opportunity and at one time it was estimated 150 shops were run – quite illegally – from homes on the Estate.

There was little landscaping and a great deal of uniformity in the housing. The well-intentioned layout, which did reflect garden city ideals of circles, crescents and cul-de-sacs, only added to the confusion. The Corporation erected four illuminated signs at the entrances to the Estate to assist those who got lost.

The first school didn’t open until 1929 – free bus and tram tickets were provided to get children to inner-city schools (though many stayed at home). The first Catholic school didn’t open until 1933. More seriously, to some of the residents, there was no Catholic church until 1928, a temporary structure until a permanent building opened nine years later. (3)

It was sinful not to build a church for the people at the same time as they built the houses. We needed communion and the confessional just as much as a roof over our heads.

The Council did its bit for morality by deciding in 1926 that no public houses would be permitted on its estates though the brewers soon built large premises on their fringes which were well used.

It was not all bad, however. An infant welfare centre started in 1929, a temporary library in the same year, and the first public hall built on a council estate was opened in the Broadway in 1930. Public baths followed in 1936 and the tramways were finally extended into the Estate in 1938.

The reality is that for nearly all the incoming tenants their new homes represented a massive improvement on what they had known before. In this context, downstairs bathrooms and the Estate’s teething troubles were, for the most part, readily accepted. Meanwhile an active tenants’ association campaigned for improvements. ‘Everybody complained, but they didn’t really get that upset’. (4)

Who were these new tenants? Thanks to the Corporation’s tenancy cards – and Madeline McKenna’s hard work – we know pretty precisely. Almost 80 per cent of Norris Green’s heads of household belonged to the skilled or semi-skilled working class.

The Council wanted tenants who could pay regularly and council rents demanded a good working-class income, the more so in these suburban estates where additional travel-to-work costs were high.

But in Liverpool – a city with a large amount of casual labour and with unemployment levels reaching one third of the workforce in the 1930s – this could not be sustained. Increasingly, Norris Green and the other estates did house a less skilled and less well-off working class, particularly in the cheaper non-parlour homes. Of course, many tenants – skilled and unskilled alike – also suffered unemployment in this period.

This shift was noticed by some existing tenants:

Norris Green had been alright but you had got some rather low types there, barrow women in shawls, that sort of thing.

Rents, utility bills, furniture and transport costs could become unsustainable and many of McKenna’s interviewees tell of the hard times and desperate economy measures of these years. Around 40 per cent of Norris Green tenants gave up their tenancies in this period, often because they couldn’t afford them, sometimes because they missed the closer-knit communities around their former inner-city homes.

But looking back, with some nostalgia maybe, long-term Norris Green residents all testified to a friendly and sociable estate:

There is nothing I can say I didn’t like about the district, the house or the neighbours. I have always been so happy here. My next door neighbour was a lovely person. She came from Great Homer Street and when I first saw her, I thought, oh dear, what is she going to be like. She was wearing a shawl, you see, but she tried to improve herself by asking how to say certain words and I remember when she bought her first coat, she was so proud she ran in to show me. She never wore the shawl after that. Most of the neighbours were pleasant.

Shawls obviously signified ‘rough’ working-class origins and their loss was seen as a mark of ‘respectability’. And note how clearly council estates were regarded as a vehicle of upward mobility, of benign social engineering, in fact: (7)

Our next door neighbour, Mrs Jones, they had come from Burlington Street and there were five boys and they were staunch Orange Lodge. Oh, the fights those boys used to have at first and the language but they all quietened down after a while and you know, all those boys did well, served apprenticeships. I think living among decent people pulled that type up somehow.

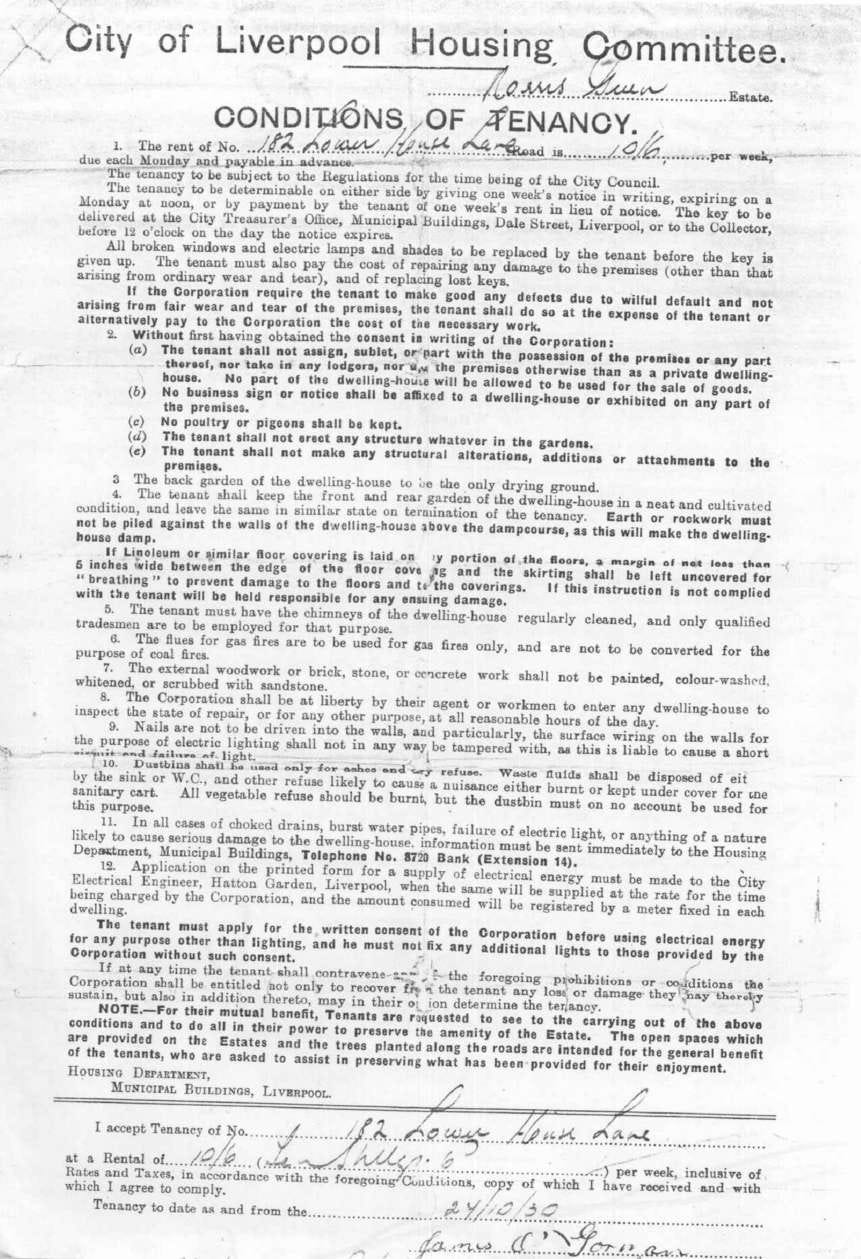

The tenancy agreement below (you’ll need to enlarge it) certainly shows the high standards that the Corporation expected of its tenants:

What happened next is that Norris Green ‘maintained its reputation as a settled and desired Corporation estate’. A 1971 survey ‘identified the strength of local ties’ and concluded: (4)

Norris Green is the most stable and respectable of the study areas. Only a small proportion of the tenants expect to move from the area, and levels of satisfaction are high. Interest in owning is strongest in Norris Green, and levels of income, social class, and savings make it likely that a proportion of young families will leave to buy.

So what did go wrong? That’s another story, to be told next week.

First published in December 2013 with added photographs taken in 2022

Sources

(1) This and some other detail below is taken from Madeline McKenna, ‘The Suburbanization of the Working-Class Population of Liverpool between the Wars’, Social History, Vol. 16, No. 2, May, 1991

(2) Vinny Timmins, A Brief History of Norris Green

(3) This and the four quotes which follow from long-term residents interviewed in 1981 are drawn from Madeline McKenna, The Development of Suburban Council Housing Estates in Liverpool between the Wars, University of Liverpool PhD, 1986

(4) Barbara Weinberger, Liverpool Estates Survey, published 1973, quoted in Richard Harris, Peter Larkham (eds), Changing Suburbs: Foundation, Form and Function (1999).

My thanks to contributors to the Yo! Liverpool forum for some of the images above.

Thanks! Yes it did. My parents were lucky to get council housing in the sixties, and our estate was majority trawlermen and associated trades. There were "problem families" but with so much work available, and strong social ties, people generally did get on well. The downside was the prejudice against people who didn't fit in (my dad worked out of town as an aircraft engineer, and had to have a car, so we were seen as 'posh") and a passive attitude to authority. We didn't have the community groups to stand up to the council when they stopped maintaining the estate. High unemployment from the mid-seventies on, and then the "right-to buy", broke up the community and also introduced lots of social issues (drugs, vandalism, stealing from neighbours) that were a big shock. One thing I do remember as a child was how matriarchal the estate was. The men were away at sea for weeks at a time and the mothers and grandmothers ruled all!

A very interesting article, and as someone who grew up in council housing in the North West I am looking forward to the second part to see if changes from the 70s onward mirror my family experiences.