The London School Board built some 400 schools in the thirty years of its existence. Together, they represent one of municipalism’s outstanding achievements. Individually, they remain impressive both as architecture and symbol.

The origins of the London School Board lay in the 1870 Education Act – the first attempt to ensure the education of working-class children. To this point, this had been a haphazard affair, relying on the voluntary efforts of the churches or generally low-quality private provision.

The Act required that sufficient schools be provided to educate all children between the ages of 5 and 13. Elected School Boards were to be established where provision by other means had proved inadequate. In London, particularly in its poorer areas, the inadequacy of current provision was so obvious that the Act required the establishment of a Board from the outset.

Education was as yet neither compulsory nor free but London (and 170 other local School Boards) passed bye-laws compelling attendance by the end of 1871 and the state itself decreed that elementary education be compulsory in 1880 and free in 1891.

Passing laws was one thing, implementing them was another. As Jerry White has argued, the new Board ‘took on the greatest administrative challenge ever faced by an arm of London government.’ (1) A detailed analysis of Census returns, supplemented by house-to-house surveys, revealed that the Board had immediately to build new schools for some 112,000 pupils.

In another context, a boast of 1092 meetings (121 meetings of the London Board and 971 subcommittee meetings) and over 1000 bye-laws passed in three years might seem a celebration of bureaucratism run wild. But by the end of 1873, the Board could point to 36 schools completed, 28 being erected, 22 contracted and a total of 79,625 pupils being schooled. (2)

Beyond this, there was a commitment to design – understood as inextricably linked to purpose – that stands to the credit of the Board and the man appointed as its architect in 1871, Edward Robert Robson. He built or supervised the building of 289 new board schools in London between 1871 and 1884.

Architecturally, there had been already a reaction against the florid neo-Gothic of the high-Victorian era. The Arts and Crafts movement was gaining influence and its impact was shown in Robson’s philosophy of design: (3)

To do ordinary buildings well, using every material rightly and justly, is the first mark of that interdependence between building and architecture which renders the higher and more intellectual efforts of the latter at all possible … Architecture is not mere display, it is not fashion, it’s not for the rich alone.

But he believed equally that the new schools were ‘henceforth to take rank as public buildings, and should be planned and built in a manner befitting their new dignity.’ In a more sonorous phrase, he described them as ‘sermons in brick’. (4)

Some may think that [Art] has no right to trouble herself where only ragged children are concerned … Yet there is a sense in which she may exert her influence in the highest and best manner. She may suitably mark a great social movement if invited to be present in the buildings … in making her mark on the schools of the people, show in some wise what the homes of the people ought to be.

He also required that the architecture of the Board Schools be secular, aiming at ‘a pointed character of civil type’ – ‘whether we like it or not, the education of the people is now governed by the lawyer rather than the clergyman’.

For these reasons, Robson sought a precedent rooted in English craft and a ‘simple brick style’. He alighted on:

the time of the Jameses, Queen Anne, and the early Georges, whatever some enthusiasts may think of its value in point of art. The buildings then approach more nearly the spirit of our own time, and are invariably true in point of construction and workmanlike feeling.

Here lay the origins of the so-called Queen Anne style of which the Board Schools are among the best examples. Architectural historians will point out that this was, in fact, an eclectic style incorporating Classical, Flemish and French Renaissance influences. But this hybridity did, nevertheless, provide a distinct and attractive appearance to the schools.

Queen Anne style had also emerged as the domestic architecture of the new middle classes. This model of bourgeois domesticity was not accidental. Robson believed:

If we can make the homes of these poor persons brighter, more interesting, nobler, by so treating the necessary Board Schools planted in their midst as to make each building undertake a sort of leavening influence, we have set on foot a permanent and ever-active good.

But he also hoped that ‘the working man’ would ‘consider the schools in the light of a property peculiarly his own, of which he may be proud, and not as an alien institution forced upon him by those of superior station’.

Still, the architecture of the new Board Schools was intended to impress and civilise. As Sherlock Holmes (or his begetter Arthur Conan Doyle) proclaimed: (5)

Lighthouses, my boy! Beacons of the future! Capsules with hundreds of bright little seeds in each, out of which will spring the wiser, better England of the future.

The schools’ presence was further enhanced by their scale and elevation. Typically, they were ‘three-decker’ – a design reflecting their three divisions of pupil: infants on the ground floor, older girls and boys taught separately on the second and third floors. Some of the schools, where the sites were unusually constrained, also had a rooftop pay area.

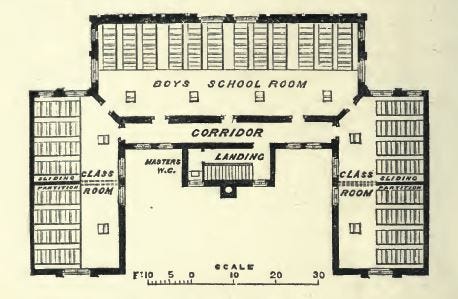

Internally, there was far less decorative effect. Originally, the schools were designed with very large classrooms in which several groups could be taught simultaneously by teacher-monitors who were thus more easily supervised.

Over time and against initial resistance to this ‘Prussian’ model, smaller, separate classrooms, each with their own teacher became the norm. There was some lag between the innovativeness of school architecture and the very traditional pedagogy it housed.

Robson’s passion for design that was both fit for purpose and inspiring went beyond the architectural. He was designing:

for children whose manners, morals, habits of order, cleanliness, and punctuality, temper, love of study and of the school, cannot fail to be in no inconsiderable degree affected by the attractive or repulsive situation, appearance, out-door convenience and in-door comfort, of the place where they are to spend a large part of the most impressionable period of their lives.

Heating, ventilation, play space, the ergonomics of desks and chairs – all fell under the architect’s punctilious eye. I’ll spare you the details, important though they are, but this gem – penned by his successor TJ Bailey, the author of another primer on school architecture – caught my eye. Writing on school playgrounds, Bailey counselled that: (6)

Projecting slabs of stone (millstone grit by preference) should also be built into the walls at intervals for sharpening slate pencils, as otherwise the brickwork is liable to be utilised for this purpose and so become defaced.

Whatever the bigger picture, there’s something impressive about that concern for detail.

Much more could be said (and has) about the Board Schools and early education. School Boards as a whole came to seen as an expensive and unnecessary layer of bureaucracy as local government developed and were abolished in the 1902 Education Act.

The London County Council took over the London Board’s duties in 1904. In a curious twist, when the LCC was abolished in 1965, a directly elected Inner London Education Authority was created to oversee education in the former School Board area until it too met the fate of its predecessor in 1990. Now, of course, the central state and its political masters marginalise local democracy at every turn and the proud role of locally elected bodies in promoting local schooling is neglected and maligned.

But the London School Board and the system it created deserve recognition. It met the challenge set in 1870 and it did so, architecturally, with some panache. Jerry White notes this ‘municipal self-confidence and energy’ and argues too that 1870 represented something more – it marked ‘a huge expansion in London’s public sphere and … the moment when the balance tipped from Church to state in the organisation of public affairs.’ We neglect this history at our peril.

Sources

(1) Jerry White, London in the Nineteenth Century (2007)

(2) School Board for London, The Work of Three Years, 1870-1873

(3) ER Robson, School Architecture (1874). The following quotes from Robson come from the same source unless otherwise indicated.

(4) ER Robson, ‘Art as applied to town schools’, Art Journal, 1881

(5) Cited in Deborah Weiner, Architecture and Social Reform in Late-Victorian London (1994)

(6) TJ Bailey, The Planning and Construction of Board Schools (1900)