I have a soft spot for Bermondsey and we’re back there again. This is a short article about a tiny estate but Bermondsey Labour Party had come to the conclusion that small was beautiful well before EF Schumacher.

The Council naturally sought health and well-being for its population but it aspired to beauty too – as this earlier post explains. Living in one of the most densely-settled, slum-ridden and industrialised boroughs of London, Bermondsey’s Labour activists sought to raise the conditions of the people by all means possible.

Slum clearance and rebuilding were, of course, a major priority and it was the nexus of the two that best reveals Bermondsey Labour’s unique brand of political idealism.

In large part, this special quality to local Labour politics reflected the personality of its principal figures, Dr Alfred Salter and his wife Ada. They had joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1908, convinced that nothing other than outright socialism could fulfil their Christian idealism and transform the conditions of the people among whom they lived and worked.

Seven ILP candidates contested Bermondsey’s council elections in 1910 but just one – Ada Salter – was victorious. From this small beginning, Alfred announced his dream:

We’ll pull down three-quarters of Bermondsey and build a garden city in its place.

When Labour did win power – it secured a majority on the council in 1922 – that essential vision remained in place and its first test was to be the clearance of a notorious area of condemned housing in Salisbury Street.

These four acres housed some 1300 people. Death rates from respiratory disease were three times the London average, the infant death rate twice the London average. That the housing should be cleared was not in doubt – it had been condemned thirty years earlier. The issue was what would replace it.

Bermondsey Labour’s 1922 election address had been explicit:

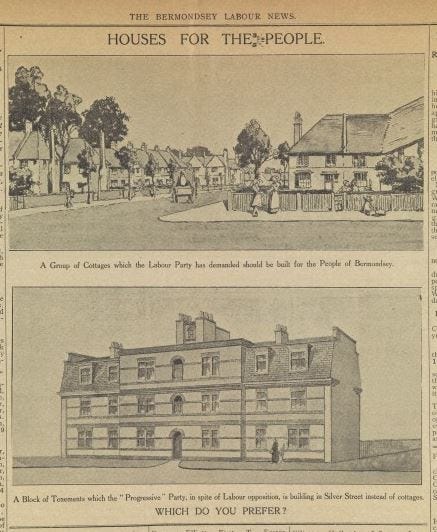

The Labour Party stands for a cottage home for every family, and though this may not be possible at the present moment, we shall work and fight for measures tending to that end. No more Progressive barracks and Coalition skyscrapers!

The high-rise developments they decried were the tenement blocks that were being built to rehouse many working-class families in inner-city London. The plan to transform Bermondsey into a garden city was not to be compromised.

Instead of tenements, Labour proposed a small estate of 54 cottages – ‘trim structures of warm, red brick, some with bay windows, others with recessed doorways, sheltered by an arched doorway’. Each would have three bedrooms, a living room, scullery, larder, bathroom and lavatory with hot and cold water. The new estate would house around 400 people.

The estate’s designer was Ewart G Culpin – a leader of the Garden City movement and later a prominent Labour member of the London County Council (LCC). He would go on to design the modernist Poplar New Town Hall which I’ve written about previously.

In the years immediately after the First World War, this policy of Bermondsey’s was in line with that of the London Labour movement more widely and Salter’s radicalism wasn’t quite so far-fetched. Herbert Morrison had expressed the party’s official policy to the LCC in May 1918 – their object was to: (1)

break up London as we know it, to encourage the exodus outwards…and to plan a wide outer ring on garden city principles…We would build no more tenements…we would build new towns where possible, or garden suburbs where that was the best we could do.

But practically by the early twenties, there was significant opposition to Bermondsey’s proposal for Salisbury Street. A small scheme catering for 400 left some 900 of the current residents displaced. The LCC – then under Conservative control in the guise of the Municipal Reform Party – protested that the plans would:

create not only hardship to…such persons who would have to be accommodated elsewhere, but an unnecessarily large burden on the community for the sake of the favoured few who would be housed in the cottages.

In fact, neighbouring borough councils were also anxious, fearing that any displaced residents of Bermondsey would simply add to their own problems of overcrowding.

The Ministry of Health – responsible for housebuilding subsidies – blocked the proposals and requested the council submit a tenement scheme which would rehouse more people in the borough.

Bermondsey, though, had ‘decided that it would not put up anything of which it would be ashamed’ – ‘it steadfastly refused to warehouse the people in barracks’.

And it won. The short-lived Labour government of 1924 and Minister of Health, John Wheatley, sanctioned the scheme. Work began the following year and the estate was officially opened in November 1928, built by direct labour at a cost of £550 per dwelling.

There was justifiable pride in the scheme, made sweeter by the victory won. The mayor spoke of a:

magnificent piece of social improvement…We have cleared forever one terrible blot on our civic conscience, and we intend to go on steadily with the good work we have started until there is no place in the borough upon which we can reproach ourselves

He boasted £2000 collected in rents and not a penny in arrears: ‘We find that the people have responded magnificently to the Council’s efforts on their behalf, and they are taking infinitely more pride in their homes than ever before’.

There you have the early Labour Party’s paradoxical mix of paternalism and self-improvement in a nutshell. Ironically, it’s middle-class academics and some self-styled revolutionaries who feel most affronted by it. I’d simply point out that this was a conversation occurring within the working class.

If you visit the area today, you’ll find the estate between the new (1999) Bermondsey tube station and the river. And you’ll notice that Bermondsey is not a garden city. The Wilson Grove estate – a new identity to mark the distinction with its past – was the high-water mark of local Labour garden city ideals.

Plans for a second, similar, estate in Vauban Street were blocked and the Ministry once more demanded tenements. Salter stated grandiloquently that Bermondsey would ‘refuse to commit this crime against humanity’. But over time a more pragmatic approach developed.

The garden city ideal remained potent and garden suburbs in the interwar period (such as Becontree and Wythenshawe) and New Towns in the postwar period testify to its lingering power. But the need to rehouse inner-city populations more quickly and on a larger scale and the desire of Labour politicians to provide such larger solutions did – you don’t need to be told – lead to the embrace of multi-storey housing.

Unavoidable pragmatism and well-meaning ambition did, in the end, trump the principled resolution of Labour councillors such as those in Bermondsey to provide ‘cottage homes’ for all.

Back in 1928, speaking at the opening ceremony of Wilson Grove, Alfred Salter, now constituency MP, praised the foresight of the council:

that foresight – looking to the future and not only the present – not hurriedly throwing up dwellings which in 50 years’ time will become slums and therefore a disgrace to civilisation…

Having experienced some of the worst mistakes of postwar high-rise, I think we can grant him some perspicacity and the council some credit.

Sources:

(1) This and the quotation which follows come from JA Yelling, Slums and Redevelopment: Policy and Practice in England, 1918-45 (1993)

Most other contemporary quotations come from contemporary election addresses and newspaper reports provided by the excellent Southwark Local History Library, also the original source of the older images used.