Victoria Park in east London, a park inaugurated under royal patronage in 1840, hardly seems to qualify as a municipal dream. But it has a proud democratic history – it’s earned its nickname, the People’s Park – and has flourished under municipal patronage for many years. It deserves its place.

Still, let’s begin by exploring those early years and the involvement of the Great and the Good. The first annual report of the Registrar-General of Births, Deaths and Marriages in 1839 contained an appendix by William Farr:(1)

A park in the East End of London would probably diminish the annual deaths by several thousands … and add several years to the lives of the entire population. The poorer classes would be benefited by these measures, and the poor rates reduced.

His words sparked a response. George Frederick Young, a shipbuilder and MP for Tynemouth but with local connections, called a public meeting to call for a park in June 1840. Within weeks a petition of some 30,000 signatures in support and a very obsequious letter were sent to Queen Victoria. Her apparent sympathy caused the government to act.

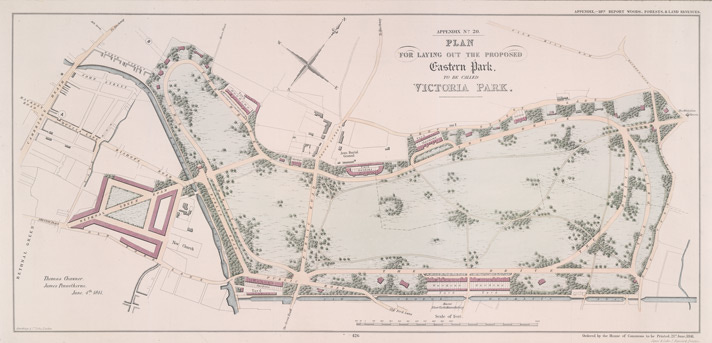

An act of parliament to create a Royal Park was passed in 1841 and land procured – making use of the existing open space of Bonner’s Fields and a further expanse of brick fields, market gardens, gravel pits and farmland. James Pennethorne, the architect of the Office of the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, was commissioned to design the new park.

By the mid-40s, as construction and planting continued, the park was open. There was no official ceremony, ‘no feast of oratory and ceremonial to gladden the hearts of the East Enders. They just took the park over in 1845 and used it’. (2) The first victory for the people.

In other respects too, popular action brought response. There was no bathing pool provided and local youths were in the habit of bathing – naked! – in the adjacent Regent’s Canal. Attempts to police such shocking behaviour were unavailing and within a few years a pool was provided in the park itself.

The upper classes professed themselves pleased with the effects of the park on local manners:(3)

… much good has been produced in this way I can most confidently state. Many a man whom I was accustomed to see passing the Sunday in utter idleness, smoking at his door in his shirt sleeves, unwashed and unshaven, now dresses himself as neatly and cleanly as he is able, and with his wife or children is seen walking in the park on the Sunday evening.

Whether Mr Alston, the author of this letter to the Times in 1847, showed the same equanimity in the following year – the year the Chartists delivered their third petition to parliament calling for universal manhood suffrage – is doubtful. The authorities certainly didn’t. A ‘monster meeting’ in the park on June 12 was to be a prelude to a mass march on parliament. Force of numbers was to prevail where reason and justice had failed.

This smelt of revolution and the government took all necessary measures. The meeting was declared illegal and 1600 foot police, 100 mounted police, 500 recalled police pensioners and the cavalry of the 1st Life Guards were stationed in and around the park. That show of force and the English weather – a terrific thunderstorm dispersed the few stragglers who had ignored the Chartists’ decision to cancel the meeting – prevailed. M’Douall, the Chartist leader, observed no incidents that day ‘except dreadful hooting and groaning at the mounted police’.(4)

If the British working classes never ever seemed quite so threatening again, their interest in reform remained and the park became a renowned venue for socialist meetings. An attempt to ban public meetings in the park without written permission in 1862 was simply unenforceable as was a later attempt in 1888 prohibiting collections. A rough democracy was in action.

A roll call of an alternative ‘Great and Good’ spoke – Annie Besant, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett … and William Morris who declared the park ‘rather a pretty place with water (dirty though) and lots of trees’. He complained that his pitch was ‘made noisy by other meetings, also a band not far off’ but, as up to 300 to 400 might attend these meetings, it was necessary to persevere.(5)

It’s true that fascist meetings were held in the park in the thirties but fascism has never gone uncontested. The British Union of Fascists’ march through the Jewish East End in October 1936 which had Victoria Park as its destination was halted in Cable Street. Rock Against Racism’s first gig was held in the park in April 1978, attended by a crowd of 80,000.

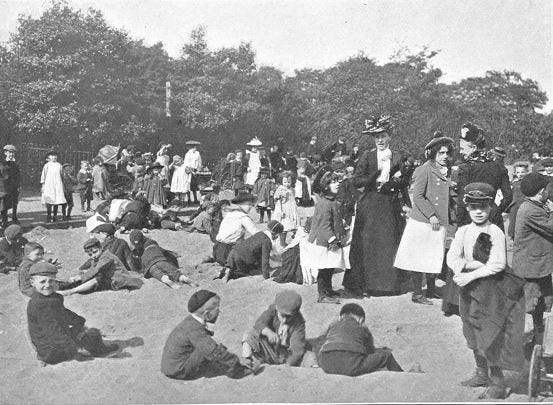

Still, let’s not forget that the park’s first function has always been as an escape from struggle and the daily grind. The East End’s greatest socialist, George Lansbury, recalled how ‘we Lansbury children loved Victoria Park and enjoyed every minute we spent there’. In fact, they were convinced that the pagoda in the park was inhabited by real Chinamen who came out at night to feed the swans and geese on the boating pool.

The pagoda Lansbury remembers, erected in 1875, was demolished in 1956. Another feature of the Park was the Victoria Fountain, donated by philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts in 1862 at a cost of £6000.

The most popular amenity, however, and one that can be credited to municipalism since the park was taken over by the London County Council in 1892, was the swimming baths opened in 1936, 200 feet long with room for up to a thousand.

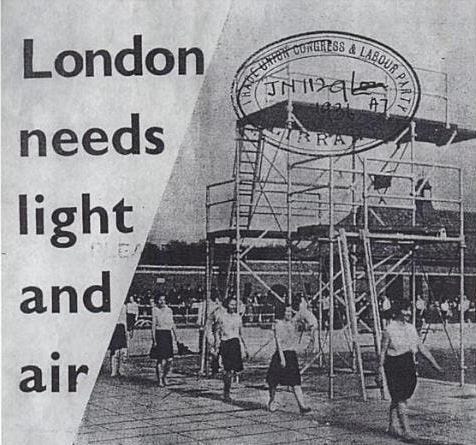

Herbert Morrison, the Labour leader of the LCC since 1934, declared ‘this is more than a swimming pool, it is East London’s own lido’. Dick Coppock, trades unionist chair of the LCC’s Parks Committee, declared the pool:

as good as anything around London owned privately and let out to bathers at twice the price … We shall bring the seaside to East London. Why this is as good as Margate.

It was part of a three-year ‘Labour Plan of Health for London’ – ‘a London with fields right round it, with more parks and playgrounds and swimming pools than any other city in the world’. (6)

Sadly, it closed permanently in 1989 and hasn’t been replaced. But the pagoda has. A major, lottery-funded, £12m refurbishment of the park was unveiled by the Mayor of Tower Hamlets in May 2012. The borough took over responsibility for the park in 1986 after the abolition of the Greater London Council, initially with Hackney but solely since 1994. He declared it the borough’s ‘jewel in the crown’.(7)

Today the park looks good. The fountain too has been restored. Boats have returned to the West Lake, fish to the East. A new community facility and café have been opened and a large adventure playground and ‘wheelpark’ (for skateboarders and BMX riders) for youngsters.

The author of this 1872 ballad to the park might not have envisaged all this but he surely wouldn’t have objected too much.

The Park is called the People’s Park

And all the walks are theirs

And strolling through the flowery paths

They breathe exotic airs,

South Kensington, let it remain

Among the Upper Ten.

East London, with useful things,

Be left with working men.

The rich should ponder on the fact

Tis labour has built it up

A mountain of prodigious wealth

And filled the golden cup.

And surely workers who have toiled

Are worthy to behold

Some portion of the treasures won

And ribs of shining gold.

‘Vicky Park’ is, in every sense, ‘owned’ by the people. Strangely that was true even in its days as a Royal Park – it is still technically Crown land – under the improving management of the upper classes. It is truer today in municipal hands.

Sources

(1) Quoted in Charles Poulsen, Victoria Park. A Study in the History of East London (1976)

(2) Charles Poulsen, Victoria Park. A Study in the History of East London (1976)

(3) Letter to the Times, 7 September, 1847, quoted in The Dictionary of Victorian London

(4) Quoted in David Goodway, London Chartism, 1838-1848 (2002)

(5) Quoted in Rosemary Taylor, ‘The City of Dreadful Delight: William Morris in the East End of London‘

(6) A London Labour Party leaflet included in Raphael Samuel, Island Stories: Untravelling Britain (1999)

(7) Quoted in the Victoria Park Project Newsletter, October 2012

A lovely place (and article), though the place was very crowded the only time I was there. At that inaugural Anti-Nazi League gig!