There were those who looked askance at the London County Council’s new Dover House Estate in 1919. Well-heeled local people in the big houses nearby expressed concern that transport links were poor for the area’s new residents. And then there was another ‘element for consideration’ – ‘that its conversion into a working-class district must enormously depreciate the rateable value of property in the vicinity’. (1)

In fact, worries that the Estate would blight the neighbourhood and would be filled by ‘very, very poor people from the bad areas of the East End’ were illusory. The Dover House Estate, initially known as the Roehampton Estate, would become a ‘show place in its day … visited by many from all over the world.’ (2)

And it would house an overwhelmingly ‘respectable’ working class. Many of these worked in the public services – in public transport, as police officers or postal workers – and they would give the Estate its occasional nickname. We saw in Bristol the high standards of the earliest council housing built after World War One when ‘homes for heroes’ was briefly something more than a slogan. The Dover House Estate is a London equivalent and, as Mark Swenarton noted, it would ‘set the standard for LCC building in general’. (3)

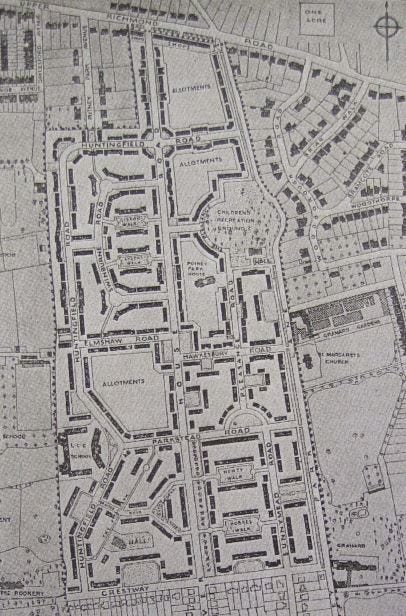

In 1919, the LCC bought – its first post-war purchase – 147 acres of parkland belonging to the adjacent private estates of Dover House and Putney Park House. The former was demolished but the latter survived as a social centre – the ‘Rec’ to local residents – for the new estate. It’s been sold off now and converted into private flats. Building began in early 1920 under the generous subsidies of Addison’s 1919 Housing and Town Planning Act. By July 1921, when the Addison scheme was axed, just 17 houses had been completed. These cost £1150 each; in all 634 would be built under the terms of this initial contract until terminated as construction costs fell.

A further 168 homes were built in 1924 under Chamberlain’s Housing Act and more followed under the Wheatley Act of that year. By 1927, when the Estate was complete, 1212 homes had been erected – ranging from five-room houses to two-room flats, accommodating a population of around 4400. (4) Size and quality deteriorated as the Estate expanded and Government subsidies and prescribed housing standards fell:

As financial problems arose so each new builder made the houses smaller as they went up the hill. They were smaller and smaller so that when you got to the top ones … if you opened the front door you had to close all the other doors, you know, otherwise you couldn’t get in.

The homes themselves built of stock brick with occasional decorative touches and roughcast rendering to bring variety. Doors and porches were used to add to the ‘cottagey’ feel of the housing. Rooflines – a range of gable and hipped ends, some houses with first-floor eaves and dormer windows – are varied strikingly, their visual impact heightened by the planners’ deliberate use of the Estate’s sloping landscape.

Internally, the homes were of their time – gas-lit in the first place with water heated in a downstairs coal-fired copper and pumped upstairs where necessary. But every home had a garden and many, unusually, had a side garden – another feature deliberately employed by the planners to add to the Estate’s vistas and feeling of spaciousness. (5)

But the real glory of the Dover House Estate lay in its overall design and layout. The 1921 estate plan shows how carefully its design conforms to Garden City ideals in its studied informality, open space and greenery, and curving streetscapes.

‘A prime objective’ of the LCC’s planners was that ‘each group of houses should overlook or have access to a small open space close by’. Some of the cottages are arranged around greens but, even in the more conventional streets, terraces are short, often set back, with clusters of homes possessing an intimacy and identity. Mature trees were retained and new ones planted. Footways included wide grass verges – though the latter have fallen to the need for on-street parking, as some of the beautiful front gardens have been converted into hardstanding.

The Pleasance formed the Estate’s major open space but the nine acres set aside for allotments in the Estate were, in their way, an even stronger statement of Garden City ideals – an echo, at least, of Ebenezer Howard’s dream of healthy and self-sufficient living. Two of the three allotment areas initially provided survive; one has been used for in-fill housing.

Huntingfield Road Elementary School, opened in March 1925, would be another key institution, especially when – in its early years – the Estate was home to so many young families. The school’s single-storey design was another testament to the Garden City ideal of healthy living, being described by the LCC as ‘a pavilion type’, approximating ‘to the lines of a sanatorium’. (6) It closed in 1993.

In other respects, community facilities were lacking. A small row of shops was set at the periphery of the Estate but proved expensive even for better-off residents. There was no library, no health centre. No public houses either though those who found ‘the Rec’ too stuffy could walk to traditional pubs in Upper Richmond Road or Roehampton Village.

This was, in any case, a new community – literally in that the Estate’s new residents had moved from densely-settled inner-city areas but psychologically too. Looking back, older residents are quick to praise a traditional neighbourliness which existed in these years. Two residents recall:

People left their doors open, their back doors open. You didn’t have to worry then, you see. There was no problem.

I mean my mum had to go off to hospital quite a bit … And automatically there would always be a neighbour to look after you until your mum came back. And you know that was just the way things happened.

But many acknowledge too – in almost identical terms – a shift:

People were friendly, but they kept themselves to themselves.

Just neighbourly you were, you talked and all that but you didn’t get that far with them.

We had very good neighbours, you know we’d help each other out. But it wasn’t like, not like the community spirit that you got in the East End.

I don’t think we were ever quite like the East End with the going in and out like that.

This was a new working class whose living conditions and relative affluence combined with a self-conscious ‘respectability’ to create a more domesticated and private life-style, one that knowingly and happily distanced itself from the old intimacies of slum living. We saw this in the Wythenshawe Estate, Manchester, too.

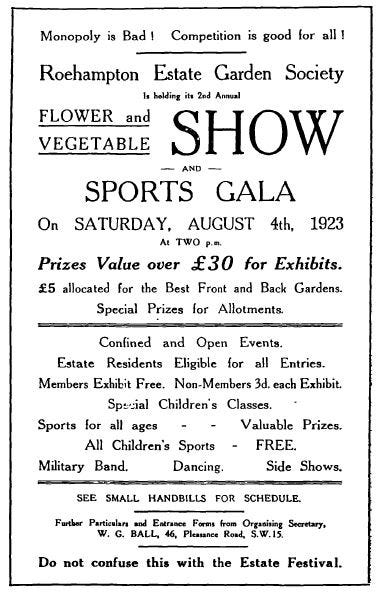

And as at Wythenshawe, gardening was a key indicator of the new way of life.

At its most explicit, this feeling of difference translated into a sense that the new residents of the Dover House Estate were – quite literally – ‘chosen people’:

The earliest people here were chosen … They were chosen to come because they all had a steady job, and they were also chosen on what they looked like. They, they were very careful who they brought here. You just couldn’t move here because you said you wanted to live here.

The LCC was as careful in selecting its tenants as that memory suggests. Prospective tenants were expected to demonstrate a ‘good record for cleanliness and punctual payment of rent’ and have an income at least five times greater than the total of rent, rates and fares. (7) In the Dover House Estate, where in 1927 some rents for houses built in its early years reached 30s (£1.50) a week, this was a considerable hurdle.

It was, therefore, those in what were called at the time ‘the sheltered trades’ – various forms of public sector employment – who were best able to fit these criteria. In fact, ten percent of the homes were initially reserved for council employees. Locals: (8)

gave us the name ‘Uniform Town’ because we had bus drivers, policemen, tram drivers and postmen living on the estate. When we walked into the village one of the locals would say ‘Hello, here comes Uniform Town’. It was all in good fun.

In fact, in 1931 the LCC estimated that an incredible – for a council estate – 37 per cent of heads of household were white-collar workers whilst 34 per cent belonged to the skilled working class. Some families even had maids. So striking was this that in 1932 the council suggested that 201 of the more ‘well-to-do tenants’ move, presumably to houses that they could afford to purchase.

Still, selection criteria remained strict. A fall in white-collar households – to 21 per cent in 1939 – was offset by an eleven per cent rise in skilled working-class heads. A smaller rise of unskilled heads had brought their total up to one quarter of the Estate as a whole – a small impact compared to that seen in Norris Green, Liverpool and the Knowle Estate in Bristol in the 1930s as Government slum clearance policies took effect.

In many ways, the rather ‘select’ air of the Estate seems to have survived to the present. This is not a tale of ‘decline’, a charting of the new realities of council housing as it became increasingly reserved for the least well-off and most disadvantaged of our community.

The sheer quality of the Dover House Estate’s design values and layout survives – protected since 1978 by its designation as a conservation area. I suppose it’s a sign of the times – not necessarily a welcome one – that a homes and property article can describe the Estate as ‘a charming enclave on the western edge of Putney’.(9)

Of course, right to buy has had a significant impact but the overall impression of the Estate now is that of a settled community. One local survey showed over 50 per cent of respondents as over 50 – probably a skewed statistic but still a sign of a community which has, in a sense, grown old with the Estate. Over half of respondents had lived on the Estate over ten years and, hearteningly, some three-quarters wanted to stay at least another five years, many permanently. (10)

There were complaints about the traffic and rat-running, people wanted better facilities for children and older people but few thought that the Estate had changed for the worse and as many thought it had improved in recent years.

We’ll let those views and that experience stand as testimony to the quality of the original design and the ideals which informed it – a moment when aesthetics briefly triumphed over economy in the design of working-class housing and a time when council housing was viewed as a step-up not a safety net.

Postscript

Michael Gilson’s book, Behind the Privet Hedge, tells the fascinating story of Richard Sudell and his central role in the development of the twentieth century suburban garden. Sudell was secretary of the Roehampton Garden Society in its earliest years.

First published in June 2014. Some later photographs added.

Sources

(1) Archibald D. Dawnay (Mayor of Wandsworth), ‘A Roehampton Estate’, letter to The Times, 15 April 1919

(2) Local residents quoted in Darrin Bayliss, Council Cottages and Community in Interwar Britain: A Study of Class, Culture, Community and Place, Queen Mary and Westfield College PhD, 1998. The quotations which follow from local people are also taken from this source as is occupational data on the Estate’s tenants.

(3) Mark Swenarton, Homes Fit for Heroes: the politics and architecture of early state housing in Britain (1981)

(4) Barbara Sanders, ‘Roehampton Council Housing Estates’, March 2004

(5) Most of the descriptive detail on the Estate here is drawn from Wandsworth Council, Dover House Estate Conservation Area Appraisal (ND)

(6) Quoted in Geraint Franklin, Inner London Schools, 1918-1944. A Thematic Study, English Heritage (2009)

(7) Mark Swenarton, Homes Fit for Heroes

(8) Quoted in Antonia Rubinstein, Just Like the Country. Memories of London families who settled the new cottage estates, 1919-1939 (1991)

(9) Anthea Masey, ‘Spotlight on Putney: a taste of country life in the capital’, London Evening Standard, July 13 2011

(10) Stuart King’s Dover House Estate residents’ survey, Autumn 2009

My thanks to Barbara Sanders whose experience and writing has provided the background to this post and who sparked my further research.

Excellent thank you. Living in a neighbouring estate, Ashburton, as I did from birth 1952 to 1966 and going to primary school in Roehampton, this was an excellent read.